A Disaster Averted

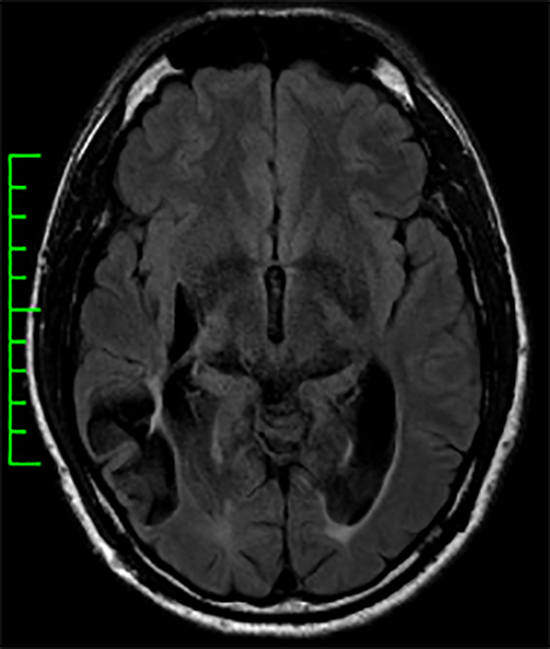

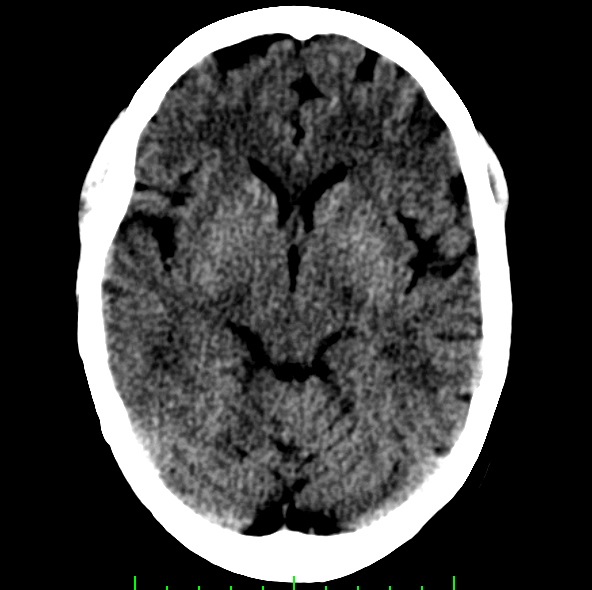

Tough to see Dural Sinus Thrombosis

March 3, 2020

For several months, a 47-year-old man with diabetes had a patch of numbness just above his left knee diagnosed to be due to nerve compression as it passes through the right groin. However, it rapidly extended to involve more of the thigh and started to feel uncomfortable. His primary doctor ordered a neurology consult, but the neurologist was not available for at least 4 weeks. His problem progressed over several days.

Frustrated by the inattention and concerned about what was happening, he was referred to me by his endocrinologist. After a thorough “intake†with me on the telephone, we arranged for an urgent evaluation due to my concern that his diabetes predisposed him to a serious problem called epidural abscess — an infection that can compress the spinal cord and cause permanent paralysis and incontinence. My evaluation showed the sensory loss on the left leg that he described, but it also revealed subtle asymptomatic changes that suggested early spinal cord compression.

I arranged for a special MRI scan planned to specifically detect epidural abscess. (Not all MRI scans are the same, and they should be ordered and planned based on what is most expected.) I then sent a note to his primary care physician alerting me to his concerns. Next. I made direct contact with the radiologist to assure that the scan was done the same day. I ensured he knew of my clinical suspicions to help him approach the scan interpretation with that important knowledge. As soon as the MRI scan was done, I had the patient send it to me so I could view it without delay. The MRI revealed the abscess, and it required urgent institution of antibiotics, close monitoring, and eventually, an operation to clean the region of infection.

The patient did well. He recovered fully. A disaster was averted.