A Missed Stroke in a Young Healthy Man

Tough to see Dural Sinus Thrombosis

March 3, 2020

Missed Right Hemispheric Stroke In a Young Professional With Anxiety and Behavioral Changes

March 3, 2020

Presentation with acute vertigo, nausea, and vomiting

A young adult man with a missed cerebellar stroke was referred to me. He had been hospitalized for acute vertigo, nausea and vomiting starting several days after new onset headaches. He had largely improved after several days. His work-up in the hospital was reportedly negative. He was discharged with the diagnosis of labyrinthitis, vomiting, and dehydration.

Referral to me for a second opinion and follow-up

The patient contacted my office for a second opinion and follow-up. I called him immediately, and he indicated that he was feeling much better. However, he was still experiencing vertigo (“like being on a shipâ€Â) and difficulty walking. His headaches lingered behind his right ear. I had his family quickly gather his medical records and CT scan. I saw him the following morning.

Further clinical history and findings

The patient had no previous medical illnesses. The episode occurred acutely on the morning after rigorous exercise that included working with free weights. His examination demonstrated gaze-directed and down-beat nystagmus. These are are abnormal eye movements that show jerking of the eyes when looking to the right, left, and downward. He had a wide-based gait (legs spread wider than normal). Also, he had dysmetria (incoordination) of the right arm and leg. These physical findings were consistent with a problem with the cerebellum.

Brain imaging

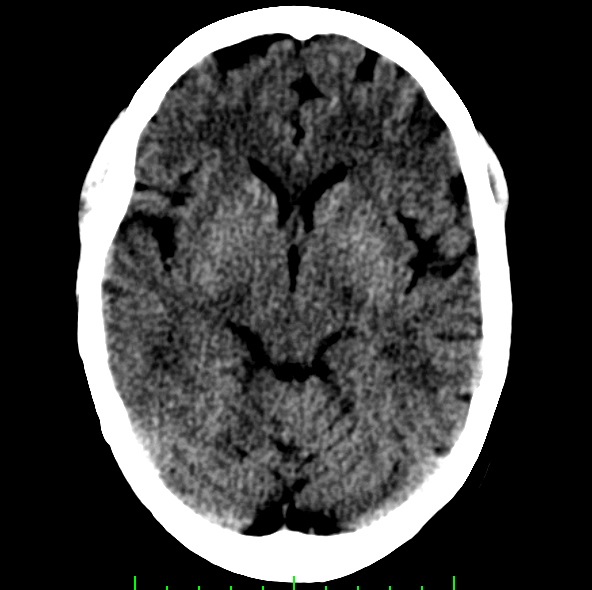

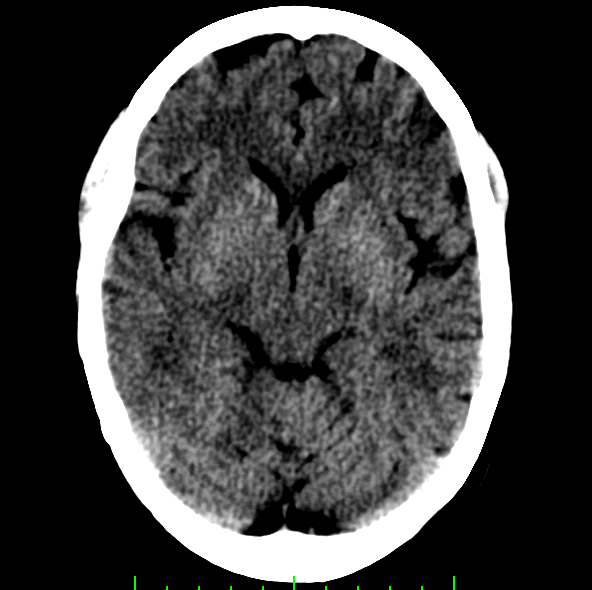

Review of the CT scan that had been read as normal showed an abnormality involving the right cerebellum.

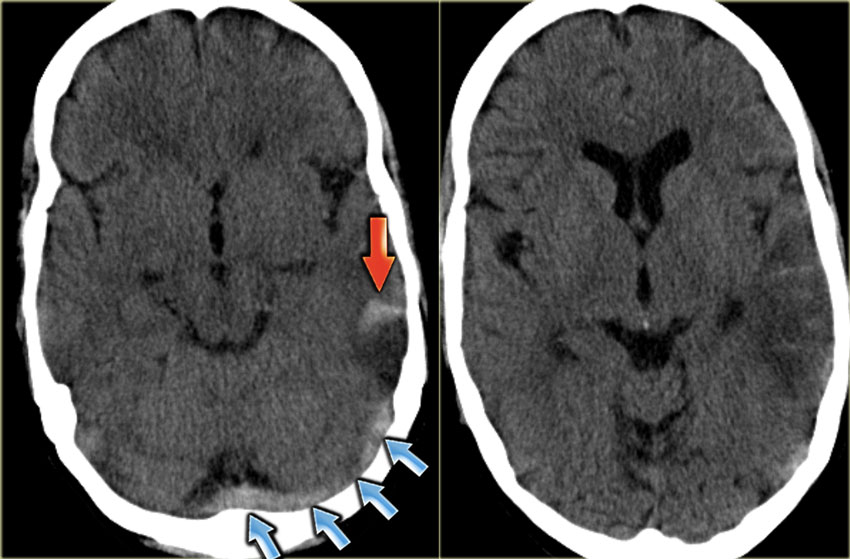

Subtle Ischemic Stroke Visible In the Right Superior Cerebellar Artery Territory

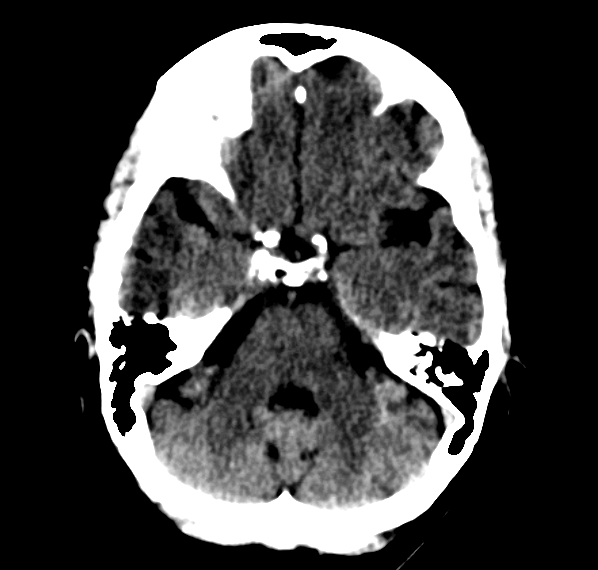

The CT scan image above shows an area of darkening on the right side in the region of the right superior cerebellum. The CT scan image below shows that the 4th ventricle on the right looks asymmetric with some flattening of the lateral recess. Both of these scans (above and below) suggest a missed cerebellar stroke.

Brain CT scan showing compression of the lateral recess of the 4th ventricle on the right

More specifically, these changes showed an acute right cerebellar cerebral infarction (ischemic stroke) in the right superior cerebellar artery territory. Given the occurrence after vigorous exercise with subsequent neck pain, I suspected that he had a right vertebral artery dissection — a tear in the inner lining of this important artery that supplies blood flow to the brain stem, cerebellum, and the occipital lobes.

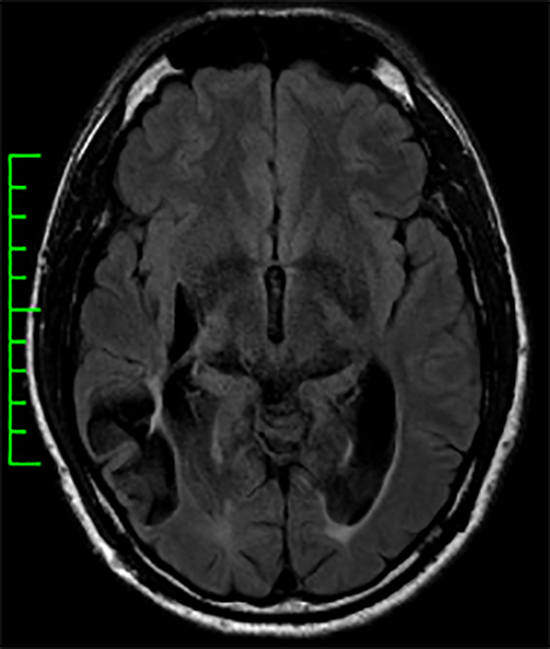

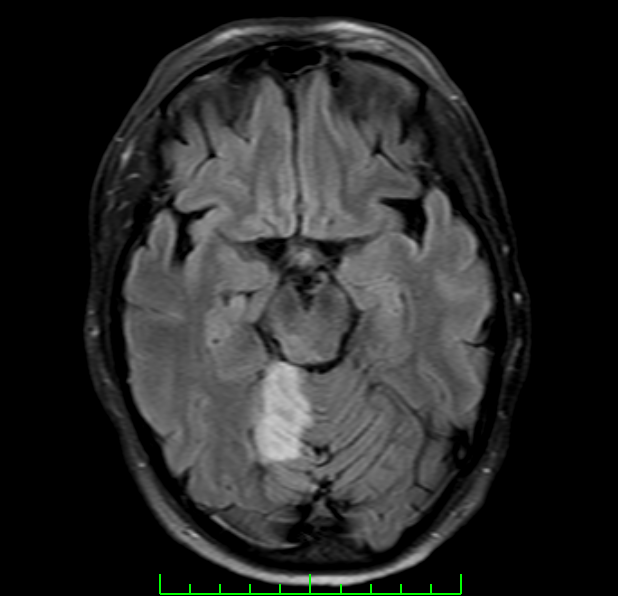

An MRI confirmed the missed cerebellar stroke (the bright area on the MRI scan below) as well as the right vertebral artery dissection.

Brain MRI scan showing acute Ischemic stroke involving the territory of the right superior cerebellar artery (SCA)

Arterial dissection and stroke

Arterial dissections involve a tear in the inner lining of an artery. This can be provoked by physical trauma and, sometimes, from excessive straining as can occur with weight-lifting. Some patients are particularly vulnerable to this complication. When the lining inside the vessel tears, clots can form inside the artery. This can lead to a complete blockage of blood flow through the artery. It can also lead to a blood clot traveling downstream to cause blockages in other arteries (called “artery-to-artery embolismâ€Â). This particular patient suffered an artery-to-artery embolism to the right superior cerebellar artery (causing an ischemic stroke of the right superior cerebellum) from a right vertebral artery dissection.

Why was his stroke initially missed?

Why did he have a missed cerebellar stroke during his acute hospitalization?

For several reasons. First, the patient is young and most health care professionals do not consider stroke as a likely problem in young patients. Second, strokes of the cerebellum do not typically present with the classical stroke signs such as language disturbance, facial weakness, visual changes, or body weakness. Third, vertigo in a young patient is much more commonly caused by non-stroke causes such as benign positional vertigo or labyrinthitis. Fourth, acute CT scans often fail to show ischemic strokes hours after the event, particularly when they involve the brain stem and/or cerebellum. If changes are present (as they were with this patient), they can be subtle. Recognizing the abnormalities often requires scan interpretation with the benefit of a clinical suspicion of a problem in this brain region based on the clinical symptoms.

How could his stroke and vertebral artery dissection have been recognized?

The proper diagnosis in this patient was possible. The temporal connection of the neurological symptoms to rigorous exercise the day before should have been considered. The location of the head pain (the region of the right vertebral artery) was also a helpful clue. The clinical findings of the gaze-directed and down beat nystagmus should have allowed the confident conclusion that the patient’s problem was not labyrinthitis. This suspicion would have been further bolstered by the finding of right-sided dysmetria. All of the findings were consistent with a problem with the cerebellum.

Final thoughts about missed cerebellar stroke

This patient was lucky. Vertebral artery dissection can lead to devastating neurological disability or death. Since he took the extra strep for further analysis, I had the opportunity to make the proper diagnosis and get him started on anticoagulants (blood thinners) to allow stabilization and healing of the vertebral artery dissection and prevention of further ischemic stroke.

Missed cerebellar ischemic strokes are far more common than one would suspect. This is even true at some of the most sophisticated Stroke Centers. This problem can be reduced through regular educational seminars with emergency department personnel (e.g., “What types of strokes don’t clinically look like strokesâ€Â). Also, doctors ordering scans should provide enough history to allow the radiologist to more carefully scrutinize brain regions that can cause the presenting clinical syndrome. And radiologists should consider the specifics of the provided history to enhance their sensitivity for recognizing subtle but relevant abnormalities.

Fortunately, with this patient, he fully recovered and we are grateful that he did not have any further stroke recurrence. The case was reviewed with the health care team involved with the patient when he was hospitalized to allow the opportunity for quality improvement.