Missed Right Hemispheric Stroke In a Young Professional With Anxiety and Behavioral Changes

A Missed Stroke in a Young Healthy Man

March 3, 2020

Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS): An Impressive Under-appreciated Treatment For Depression

March 3, 2020

Non-dominant, right hemispheric stroke in a professional young adult

I recently diagnosed a missed right hemispheric stroke in a young adult woman. She was referred to me to rule out neurological causes of anxiety and behavioral changes.

Her symptoms began one year beforehand

In retrospect, this 38 year old professional woman’s behavior changes from her missed right hemispheric stroke began one year beforehand. People in her life felt that she was behaving differently because of personal life trauma leading to anxiety. Stress from marital problems seemingly caused an abrupt decline in her work performance. As it did not improve over time, a coworker and friend suggested that she see a brain specialist. Over the preceding 6 months she had two “check-ups†with her primary care physician for anxiety that indicated that she was perfectly normal. (Right hemispheric stroke can lead to subtle changes, allowing the patient to look “perfectly normal†to friends and even to unsuspecting physicians deprived of relevant history.)

The patient is a high functioning executive. She is in charge of the creative content of major corporate projects. A friend and coworker shared that she became noticeably different one year ago. This was the likely time that she suffered what I eventually diagnosed to be a missed right hemispheric stroke. Her prior baseline was calm and organized. However, she started to complain of episodes of anxiety with accompanying palpitations and tremulousness. She had felt that these symptoms were caused by stress at work and home.

Problems in her personal life

Everyone that knew the patient believed that she had a storybook marriage. However, one year before I met her after her feelings of anxiety began, she started to have regular arguments with her husband. He shared that she abruptly “became a different person†one day when she suddenly felt he was “insincere†in his love for her. After that, she would frequently misinterpret his intentions. She appeared less animated and depressed. He felt that her facial expressions changed and suggested a new dislike for him as a person. Arguments escalated, and they separated after several months of unhappiness.

Deterioration in work quality

Around the same time, the patient’s quality of work declined. Her creative ideas were limited. Her supervision of visual layouts was poor. She was less organized. She would miss meetings and deadlines in spite of frequent reminders from her staff. This was all out of character, but they happened in lock step with her “problems at home.†Her friends and co-workers perceived that she needed time and would soon be back into her groove. Finally, when she did not “snap out of it†in spite of counseling, she was referred to me to see if there was an identifiable neurological cause to her problems.

Past history

The patient was previously healthy. She had no known medical problems. She was not on medications or supplements. She exercised regularly through running and pilates. She was not on any special fad diets, but she had a 15 pound weight loss in the past year attributed to her more regular exercise and home stress. She had been noticing palpitation for the past year and more excessive sweating. There was no family history of mental or neurological illnesses.

General examination

The patient had rapid heart beat (heart rate = 110) that was irregularly irregular. The blood pressure was normal. General examination otherwise was normal.

Neurological examination

There was a high frequency, low amplitude postural and action tremor in the arms. Her affect was blunted — seemingly without emotional expression. She was argumentative, and clearly was misreading body language. The patient could not properly demonstrate communicating and interpreting variable intention of simple verbal phrases through altered speech tone, volume, and cadence (called “expressive and receptive aprosodiaâ€Â). She had trouble solving a verbal map problem (showing “spatial disorientationâ€Â) and drawing a three dimensional box (called “constructional apraxiaâ€Â). Although the patient wore makeup, it appeared to be poorly placed and irregular in color and complexion.

On visual field testing, the patient could not perceive images in the left upper quadrant of vision with either eye. She had poor sensory localization on the left arm. There was decreased ability to identify numbers (called “agraphesthesiaâ€Â) drawn on the left hand. Also, she would ignore touch on the left side of her body (called “sensory extinctionâ€Â) when the left and right were touched together.

My clinical impression

My initial clinical impression was that this patient was in yet to be diagnosed atrial fibrillation — given her irregularly irregular heart rhythm. The tremulousness and weight loss suggested that hyperthyroidism may be the culprit for the arrhythmia.

Her neurological examination revealed right hemispheric dysfunction as reflected in:

- loss of facial animation

- difficulty with modulating and interpreting intention through non-verbal communication

- spatial disorientation

- poor left graphesthesia

- left sensory extinction

- poor application of makeup (out of character according to her friend)

- left superior quadrant visual field cut

Her argumentative nature was due to her loss of ability to express and receive intention through non-verbal cues. All of these signs are referable to impaired function of the right temporal and parietal lobes.

I postulated that the relatively acute onset of behavioral changes one year ago was likely caused by a missed non-dominant, right hemispheric stroke from paroxysmal atrial fibrillation caused by undiagnosed hyperthyroidism.This is one potential cause of stroke in a young adult.

Given the subtle nature of the manifestations of right hemispheric stroke (or right hemispheric lesions, in general), it is no surprise that there was a delay in the appreciation that this patient indeed had a brain problem.

Some relevant test results

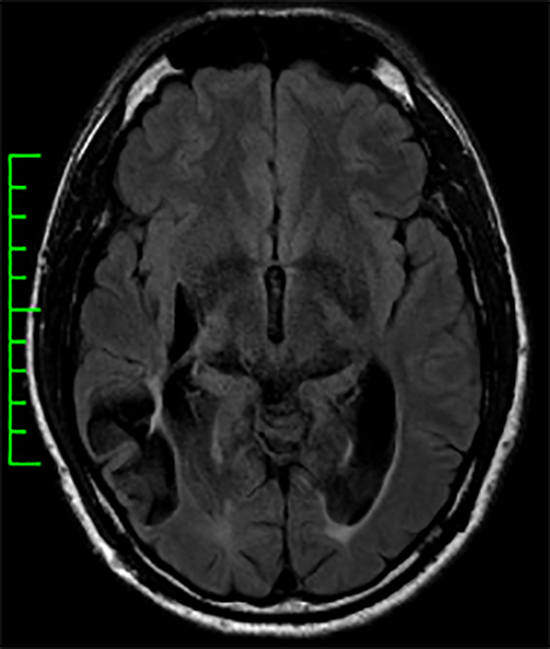

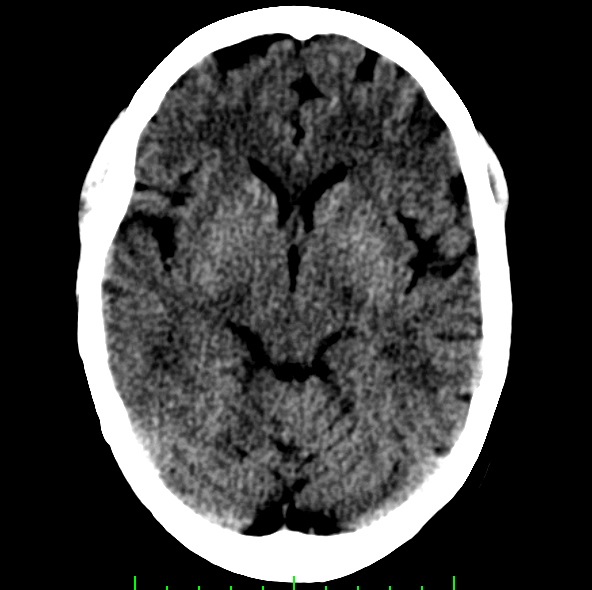

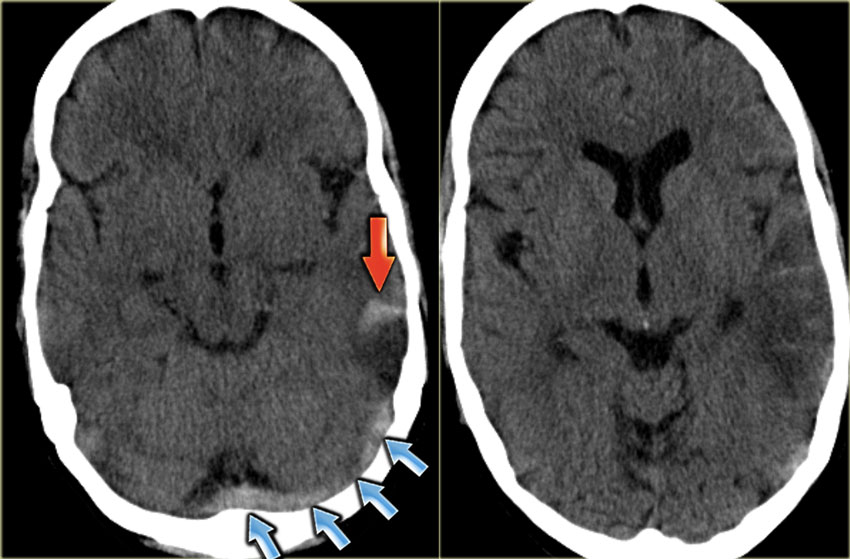

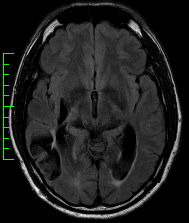

An electrocardiogram confirmed atrial fibrillation. Blood work demonstrated hyperthyroidism caused by autoimmune thyroiditis. There was no evidence of a systemic inflammatory or autoimmune process. Liver and kidney function tests were normal. An MRI scan revealed right temporal and parietal encephalomalacia from what was consistent with remote right hemispheric stroke involving the inferior division of the right middle cerebral artery.

MRI showing injury to the right posterior temporal and parietal lobes due to remote right hemispheric stroke (one year ago)

Echocardiography showed a dilated left atrium and supported her propensity for cardiogenic embolism. CT angiography of the neck and brain arteries was normal.

Why did this patient have a missed non-dominant hemispheric stroke?

The diagnosis of stroke in a young adult who is otherwise healthy is often delayed. In particular, this patient’s stroke was missed for several reasons. The non-dominant temporal and parietal regions of the brain, when injured, cause elusive manifestations. Some of these include changes in organizational skills, impaired ability to express and interpret non-verbal cues, and new visual-spatial limitations. These changes can be subtle and easily attributable to other causes such as stress and anxiety. Their behavioral correlates are easily mistaken as behavioral fluctuations commonly seen in adults. The patient’s hyperthyroidism-associated tremulousness supported the idea that the patient was dealing with stress and anxiety, even though it was actually caused by the thyroid hormone excess.

The importance of an hypothesis-guided inquiry and exam

The history shared by others and a neurological hypothesis guided examination provided the key ingredients to determining what was happening with this patient. For example, once the personal history was extracted with a neurological mindset, it led to the theory that she had right temporal-parietal dysfunction. This could explain the change in her facial animation and tendency to have more argumentative relationships. The history of the coworker helped me understand the nature of the patient’s work (very visual-spatial). It supported the theory of right temporal-parietal dysfunction also causing visual-spatial difficulties that disrupted quality work performance. This, in turn, guided my targeted examination to bring out visual-spatial difficulties, behavioral changes, subtle visual field difficulties, and cortical-based sensory integration limitations.

MRI scans do not replace neurological exams

Although the brain imaging changes in this patient were obvious, imaging abnormalities can be much more subtle with other brain pathologies in this brain region. The misconception that imaging tests (i.e., MRI scans) are the way to detect brain pathology is flawed. Patients can present with changes in these brain regions most evident through a thoughtful neurological history and examination. Brain imaging may be easily misinterpreted as “normal†and actually reflect real brain pathology only visible to discerning clinically-focused eyes by clinicians who already have a clinically-supported high index of suspicion of focal neurological dysfunction in the patient being tested.

What happened with the patient

This patient was anti-coagulated and her hyperthyroidism was treated — now on thyroid replacement. She is in sinus rhythm with return of normal dimensions of her left atrium. There has not been any stroke recurrence, and she will discontinue her anticoagulation after 6 months if there is a normal echocardiogram and continued sinus rhythm.

This young woman’s work quality has improved with targeted rehabilitation focused on her specific deficits and her professional work requirements. She now has insight into her expressive and receptive aprosodias and their impact on her relationships at work and home. She has benefited greatly from counseling to help her learn to compensate for the difficulties conveying and expressing intention. She has reconciled with her husband.

Subtleties of right temporal-parietal injury

As we are familiar with and dismissing to daily life anxiety and stress, we can become desensitized to the relevance of abrupt behavioral changes. This is especially true in young adults without a mental health history juggling the stresses of work and home. Probing into this patient’s recent work quality and problems in her social life would have readily revealed changes that could have been recognized as being potentially attributable to focal brain changes.

Doctors should always be reminded about the subtle manifestations of non-dominant, right temporal-parietal dysfunction. In addition, it is valuable to incorporate hypothesis guided history taking, neurological examination and image interpretation into clinical practice. It can enhance the sensitivity of the patient encounter and avoid delays in important diagnoses — such as right hemispheric stroke in a young adult — like happened with this patient.