Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS): An Impressive Under-appreciated Treatment For Depression

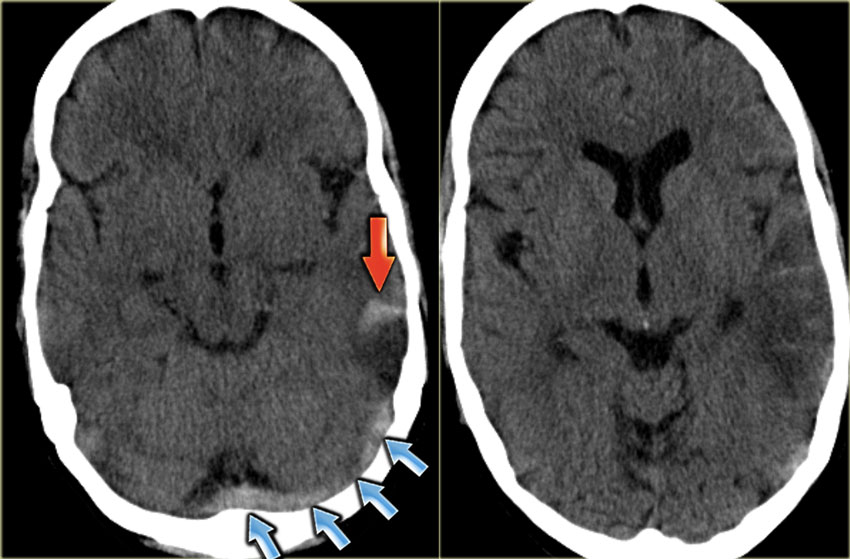

Missed Right Hemispheric Stroke In a Young Professional With Anxiety and Behavioral Changes

March 3, 2020

Background

During medical school and neurology residency in the 1980’s (before TMS existed), I was occasionally involved with the delivery of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) for functionally impaired patients with extreme depression or psychosis refractory to medical treatment. I and my colleagues would marvel at the patients’ frequent rapid recovery after ECT, but it required anesthesia, induced a generalized seizure (convulsion), and often caused long-term cognitive problems. In those days, I and my colleagues would imagine how wonderful it would be if there could be a less extreme and more localized way to electrically stimulate the brain for treatment of depression and, potentially, other neurological disorders. Now, this new way actually exists through advancement in the understanding of brain physiology in major depression and the development of TMS.

The dorsolateral prefrontal cortex frequently has decreased metabolism and blood flow in patients with major depressive disorder (MDD), and this is the target for TMS. TMS involves the use of magnetic coils to deliver targeted electromagnetic pulses to the brain. High frequency pulses are, generally, neuro-excitatory, and can lead to release of key neurotransmitters (brain chemicals) that favorably effect depressive symptoms. In other words, the advancement of brain science and technology now allow us to provide the less extreme and more localized treatment for depression we dreamed of 30 years ago through TMS!

An Overview of the Approach to TMS

TMS does not require anesthesia. Also, it does not cause a seizure for its effectiveness, nor does it cause long term cognitive problems. Patients remain awake during treatments and suffer no real side effects except, at first, mild head discomfort during the TMS treatment pulses. The efficacy and durability of TMS demonstrated in clinical trials have led to its approval as part of the armamentarium for treatment of MDD and its approval for reimbursement by most insurances in well selected patients.

The first day of TMS involves motor threshold determination and cortical mapping. In order to be effective, we must be sure that the electromagnetic field strength is strong enough to penetrate through the patient’s scalp, skull, and dura (the skin-like covering around the brain). We want it strong enough to be effective but not excessive in a way that expands the risk of seizure. The motor threshold determination is done by determining the lowest magnetic field intensity required to create a motor twitch by stimulating over the motor cortex (the part of the brain that controls movement). Once the motor threshold is established, it is time for cortical mapping.

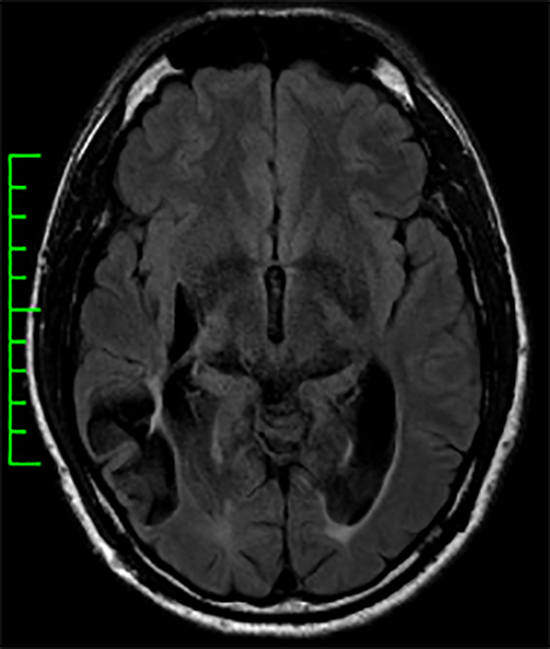

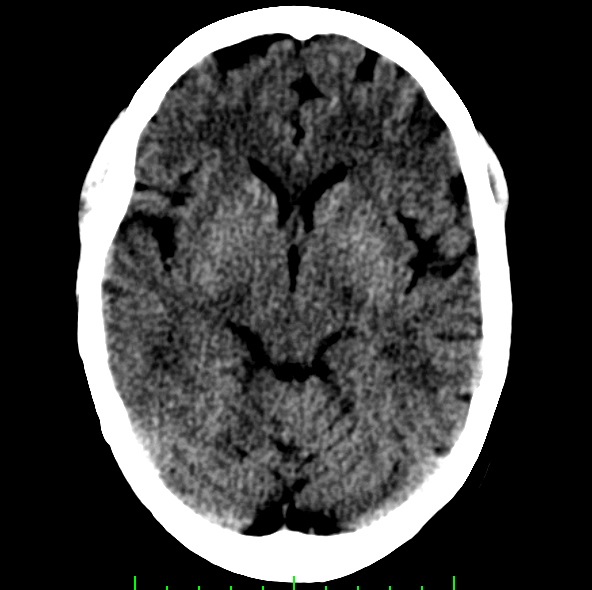

TMS cortical mapping is the technique that is employed to localize the TMS treatment. For patients with MDD, this is usually the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. Some TMS providers determine the target through various head measurements comparable to the methods used for placement of electrodes for electroencephalography (EEG = brain wave testing). Others, map the motor cortex to discover the part of the brain that controls thumb movement and then determine the TMS target through standard measurements from that region. When I deliver TMS for patients with MDD, I prefer to use both methods to establish the congruence of the targets.

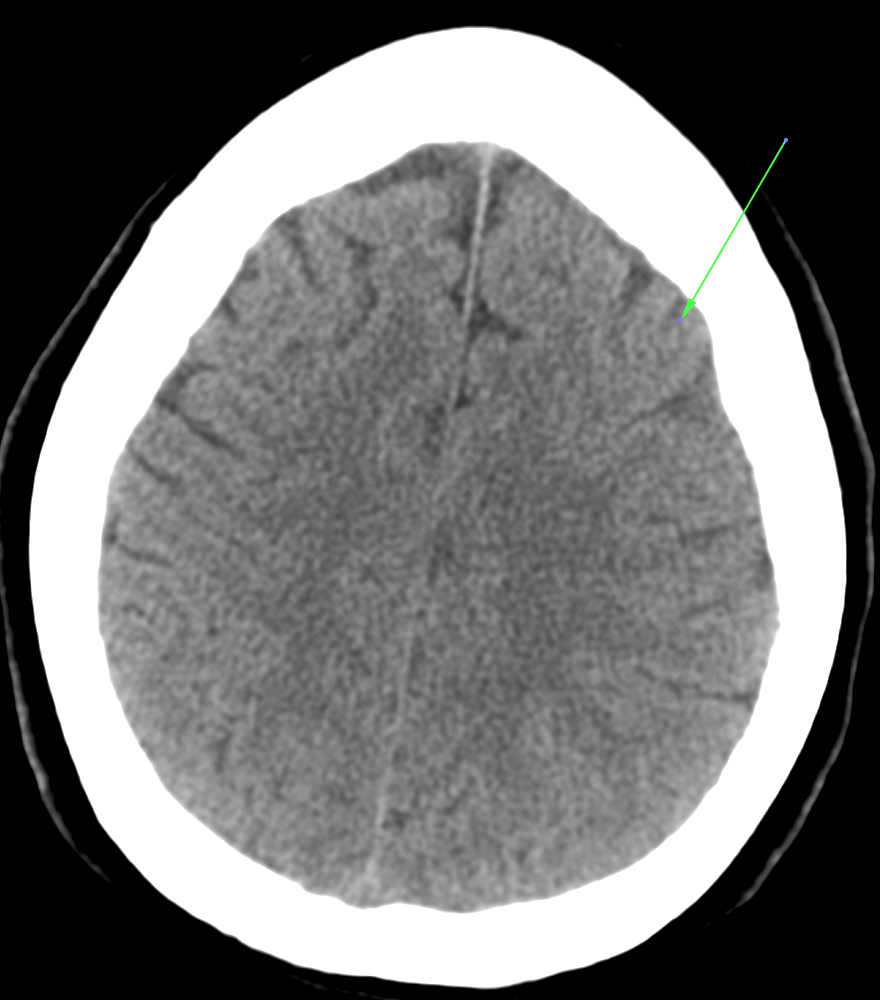

Non-contrast CT Head: The arrow is pointing to the TMS Treatment Target for Patients with MDD (Note: The rights side of the photo is the left side of the brain)

More patient-specific methods to target the TMS treatments customized to an individual’s brain anatomy and/or chemistry through advanced imaging exists and is intellectually appealing. So, it would not be a far stretch of the imagination to believe that the ready availability of this less generic approach to TMS is not too far off in the future! Clinically, it is likely that this more individualized approach to targeting TMS will lead to an important step forward in the efficacy and durability of TMS for MDD and, likely, other brain diseases.

TMS is actually more correctly referred to as rTMS, the “r†standing for repetitive. Each high frequency TMS treatment session usually involves delivery of 3000 pulses over a 20-40 minute period, and a full treatment TMS course for MDD usually involves 36 treatment sessions spread out over 6-8 weeks (typically 5 sessions/week). During this time period, the patient is able to function and work — assuming that mental health issues are not prohibitive.

TMS Treatment Systems

There are different TMS treatment systems available. The most established and studied system is called NeuroStar┞¢, manufactured by Neuronetics. The Neurostar┞¢ system allows reproducibie patient positioning, consistent individualized targeted treatment during each session, and feedback throughout a treatment session to assure consistent high-quality head contact. The importance of this contact feedback should not be underestimated. These unique qualities of the NeuroStar┞¢ TMS treatment systems are critical to optimizing the benefit of TMS treatment AND building patient and physician confidence in its consistent effectiveness. I use the NeuroStar┞¢ system for these reasons even though it is considerably more expensive on a per treatment basis relative to other systems available.

The Neurostar┞¢ TMS Treatment System Made By Neuronetics

Models of Treatment Delivery

Most TMS treatment centers use a technician-driven model for TMS treatment delivery. With this model, a physician will conduct the motor threshold determination and cortical mapping on treatment day 1, and a technician will provide the subsequent 35 treatments. While TMS technicians can be outstanding, this is not the method I use to deliver TMS.

When patients with MDD decide to receive TMS, it is a huge step. Most of these patients have been on multiple medications that have failed to provide the desired effect. The decision to move forward with TMS is a very active step and commitment. Receiving TMS requires a rigorous time commitment, adhering to a consistent schedule, and actively interacting with others. From a clinical standpoint, these steps and their relevance in the patient’s receptivity and motivation should not be underestimated. It represents a call to action from the patient and should be matched by a call to action by an experienced clinician supporting his or her efforts. Ideally, this should include the patient’s mental health providers (typically a psychiatrist and psychologist) AND a physician committed to shepherding the patient through the process with every treatment.

With this viewing point, I approach TMS differently than most providers. I have at least two prolonged sessions (2 hours each) with the patient before commencing with TMS. The first session is more medical and involves extracting a thorough medical and mental health history and conducting a comprehensive physical and neurological examination. Then, after the first visit, I make contact with the patient’s mental health providers and, sometimes, other health care providers to assure that I have an accurate view of the patient. The second visit involves a more thorough discussion about TMS to emphasize that it must be viewed as an active process that must go beyond arriving on time and passively receiving the treatments. To capitalize on the beneficial alteration in brain chemistry that is achieved by TMS, the patient must adjust various habits and lifestyle issues to optimize its benefit and achieve the best durability after the TMS treatments. So, we set to planning what those adjustments should be in cooperation with the patient’s mental health providers. Sometimes, I choose a book for us (the patient and me) to read between sessions and discuss during the treatments.

The point that I am emphasizing is that all of the steps required of the patient with MDD to participate in TMS treatment defines a state of receptivity that allows an experienced clinician to influence and optimize the benefit from TMS. The opportunity afforded by a daily interaction with the patient during these “golden†36 treatment sessions should not be squandered. Simply being kind and friendly to the patient while technically providing the TMS treatment is not enough, in my opinion. The conversations and tracking established behavioral goals during the treatment sessions should be as targeted and individualized to benefit the patient as the TMS treatment itself! So, the added benefit of TMS relative to ECT is not simply that it is targeted and less noxious. TMS also, by necessity, requires a certain active involvement of the patient that can be even further encouraged with an invigorated treatment model even though it is economically disadvantageous.

Through this more holistic approach to TMS delivery that I employ, I have observed truly exciting benefits. The patients consistently seem to “come alive†with the treatments. Within 1-2 weeks they start to become more animated and motivated. Their mood tends to become more stable. They start to become more resilient and readily “bounce back†after a more “down†or traumatic day. Medications can be wisely adjusted and lessened under the management and input of the patient’s psychiatrist and psychologist. And, with guidance and encouragement, they increasingly incorporate lifestyle changes and habits that allow them to have sustained benefit after the completion of the TMS treatments.

TMS: Why is It So Late In The Sequence of Management of Patients With MDD?

Authorization for TMS by Medicare and other insurers require the patient to meet specific qualifications. Most often, this involves proving that the patient is refractory to numerous medication trials and combinations. This approach to approval relates to the fact that the clinical efficacy trials focused on including patients with MDD who were refractory to medical therapy.

You may wonder, why is TMS one of the last chosen treatments for patients with depression before ECT? As a less invasive treatment and without all of the various side effects of medications, why isn’t it instituted earlier? The answers to these questions are complicated.

High quality counseling, cognitive and behavioral therapy, and thoughtful medication selection are clearly well-founded approaches to helping patients with depression. However, I believe that TMS should and will have an expanding role in treatment of patients with depression earlier in the course of management. Unfortunately, it will take time for clinical trials to demonstrate TMS efficacy in a broader population sequenced earlier in the treatment course. Then, it will take even more time for insurers to “catch up†and provide coverage for new treatment regimens of proven clinical efficacy.

While all medical advancements take time and research to responsibly determine their “place,†it is my hope that, in parallel, primary care physicians, mental health providers, and the general public will increasingly appreciate the benefit of TMS as an exciting addition to the treatment armamentarium for depressed patients and, eventually, other neurological and psychiatric disorders. And, even without clear data about its enhanced benefit, I will continue to use a model of treatment delivery that takes advantage of the patient’s unique receptivity and my years of clinical experience to guide their recovery in cooperation with their mental health providers.